Our Core Challenges

Uncontrolled Transhumance & illegal grazing of domestic herds

For several years, nomadic or semi-nomadic Fulani M’Bororo herders have been grazing vast herds cattle (mainly Akou breed) extensively within the protected areas of Northern Cameroon, where herding is formally prohibited. The cattle mega-herds are generally owned by wealthy businessmen and/or politicians, who are often nationals of other countries. All leaseholders and many experts in this field are in agreement that the consequences of this are devastating.

The M'Bororo cattle are generally exempt from health controls and official regional vaccination campaigns and are thus likely vectors of very serious contagious diseases that can decimate wildlife. Rinderpest, peripneumonia, anthrax and foot-and-mouth disease are widely carried and transmitted by these nomadic or semi-nomadic herds, which are sometimes considerable in number, band a deadly danger for sedentary livestock and wildlife.

There are human health risks too. Brucellosis, tuberculosis, listeriosis, salmonellosis, anthrax and even the dreaded rabies, are some of the numerous, potentially fatal, anthropology-zoonotic diseases transmitted by these herds.

As cattle, sheep, and goats carry the same contagious diseases as wild ungulates (antelopes, buffalo, giraffe, etc.), it is a matter of global conservation concern to prevent any intrusion of livestock into any of the country's national parks and protected areas, that is if we want to avoid the extinction of the populations of wild species that constitute some of the reasons for the existence of the protected habitats in the first place.

Incursions by herdsmen and their livestock in recent years is causing the rapid disappearance of lions, which are a rare African subspecies, the Northern lion, Panthera leo leo, and are in immediate danger of extinction in Cameroon and across the rest of their range.

Lions (among other predators) prefer the easy prey that the roaming cattle herds offer, and once this behaviour is learned, the lions often become repeat cattle killers. This has an intolerable economic impact on the herders who choose to poison the cattle carcasses to get rid of the "problem" and simultaneously negatively impact the entire network of carnivores and scavengers (e.g. lion, leopard, hyena, vultures, jackal, serval cat, caracal, civet, mongoose species, etc.). Similar to regular examples reported from Tanzania, Kenya, CAR, etc., we ourselves have apprehended herders with pictures of dead lions on their phones. Cattle herds and lions need to be kept apart, largely by keeping herdsmen and their livestock outside of all protected areas.

During their illegal intrusions, the herdsmen cut down an astronomical number of trees and small shrubs to feed their livestock. Notable are Afzelia africana and Isoberlinia sp., which are the preferred browse for many wild species such as the Kordofan giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis antiquorum), which according to the IUCN, is in critical danger of extinction. Similarly affected is the Lord Derby eland (Taurotragus derbianus gigas), another flagship species, which is also the main animal that attracts tourists, and is thus critical to the chain of income generation that supports the management of and operations in the protected areas, and the fight against conflicts of use & the disappearance of wildlife. Keep in mind that this wildlife constitutes a World Wildlife Heritage, as justified by its many endemic and rare species.

The scale of the migratory herds also results in overgrazing. Overgrazing reduces the diversity of grasses, such that some grass species disappear in favour of non-consumed plants that become invasive due to lack of competition. This phenomenon is well known on domestic cattle farms and in order to prevent permanent loss of diversity is managed for through pasture rotation.

Degradation of the environment and its vegetation as well as the repetitive presence of humans and domestic cattle, cause a reduction of the prime, preferred habitat for respective species, which then become more concentrated as they seek out and use smaller and smaller prime areas. This habitat-reduction and wildlife-concentration process itself results in an increased risk to wildlife populations through the increased risks of spreading diseases (as Nature tries to decrease a species' population pressure) and by being easier to target by poachers.

Loss of vegetation and transformation of vegetation cover leads to desertification and increased soil erosion by wind and water, which sediments are ultimately deposited in the water courses reducing the depth of water. Siltation and reduced water storage reduces water security, especially during drought years. Reduced water-holding capacity reduces evaporation (which reduces air moisture/rainfall levels) and endless other far-reaching consequences for all the life inhabiting the water and/or terrestrial life dependant ont the presence of water (e.g. riparian vegetation and all the wildlife that drink from rivers and/or live in the riparian vegetation zone), but also for the entire ecological integrity of the area and the entire downstream area. For example, consider the presence of hippos, they are the "lungs" of the river and they play critical ecological roles in the physical and biological functioning of the entire system.

Vegetation and soils is further directly impacted by herders and their livestock who generally use the same trails and corridors when moving through protected areas. This high and unnatural traffic leads to a significant modification of the physical structure of the soils through compaction, but vegetation is also destroyed by trampling.

All told, vegetation, soils, water dynamics, climate, etc. are intrinsically connected. Soil structure and soil health is vital to maintaining the natural vegetation cover and physical soil properties that allow for the complete functioning of many critical processes and ecosystem services. For example, the influx and storage of rainfall, rain runoff and erosion mitigation, organic and mineral nutrient storage, groundwater storage and recharge, healthy macro and micro soil-organism ecosystems (e.g. earthworms, which are a very significant element in the Faro Basin), etc. A further simple example is the penetration of rainwater into the groundwater, a process significantly aided by the presence of earthworms, which if compromised prevents the optimal maintenance of river flows in the dry season and impacts all aquatic life, fish populations, fauna, flora, and humans downstream.

The vast, transient cattle herds also aid directly to global warming through their emissions of methane (CH4), a greenhouse gas, and indirectly through their impacts on vegetation and soil and habitat transformation, compromising the sequestration of soil carbon.

In summary, any process that directly or indirectly affects vegetation and/or soil ultimately has a direct or indirect impact "up" and "down" in the cycle, and which cycle affects itself. Even a limited amount of deforestation and vegetation transformation directly affects every minute aspect of the ecology of its immediate and broader region and should be controlled at all costs.

It is important to note that many herders enter Cameroonian territory illegally, escaping all controls. Directly or indirectly, the herdsmen pose many problems for the internal security of the country and its populations. Herders are also often aggressive towards our anti-poaching units, to the extent that it has lead to murders.

Some herders are involved in smuggling weapons of war, particularly from Nigeria, and fuelling terrorist conflicts on Cameroonian soil. They cross borders along unprotected corridors, particularly inside National Parks, which are mostly devoid of wildlife and poorly monitored.

Herders entering our areas also attract gangs of violent, heavily armed and seasoned bandits who take herders hostage in order to obtain ransoms, without which they proceed to execution.

National security and criminal threats in protected, remote areas make it that much more difficult for economic operators involved in tourism compromising the creation of incomes locally and the inflow of currency at the national level. And if the system ultimately fails, it brings with it the abandonment of presence, and therefore conservation and surveillance activities of the protected areas. Current examples of this are CAR, Burkina Faso, Benin, etc.

While our projects are focussed across Northern Cameroon, our actions will have positive ecological impacts far beyond our borders. Protected area leaseholders in the equatorial forests of Cameroon have already noticed the incursions of M'Bororo herders into the forest zone, the second largest forest massif in Africa after the Democratic Republic of Congo, which ranks fifth in Africa in terms of biological diversity.

These uncontrolled illegal incursions are the direct result of decisions made in Northern Cameroon, and undermine the health of forest species, particularly that of the great apes: the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) and chimpanzees (Nigerian-Cameroonian chimpanzee from the north of the Sanaga known as Pan troglodytes ellioti and Central African chimpanzee from the south of the Sanaga known as Pan troglodytes troglodytes).

In addition to all these threats, it is important to remember that this uncontrolled influx of livestock is to the detriment of Cameroonian livestock farmers, since it represents an economic threat to the domestic cattle market.

The M’Bororo cattle are generally exempt from health controls and official regional vaccination campaigns and are thus likely vectors of very serious contagious diseases that can decimate wildlife. Rinderpest, peripneumonia, anthrax and foot-and-mouth disease are widely carried and transmitted by these nomadic or semi-nomadic herds, which are sometimes considerable in number, band a deadly danger for sedentary livestock and wildlife.

There are human health risks too. Brucellosis, tuberculosis, listeriosis, salmonellosis, anthrax and even the dreaded rabies, are some of the numerous, potentially fatal, anthropology-zoonotic diseases transmitted by these herds.

As cattle, sheep, and goats carry the same contagious diseases as wild ungulates (antelopes, buffalo, giraffe, etc.), it is a matter of global conservation concern to prevent any intrusion of livestock into any of the country’s national parks and protected areas, that is if we want to avoid the extinction of the populations of wild species that constitute some of the reasons for the existence of the protected habitats in the first place.

Incursions by herdsmen and their livestock in recent years is causing the rapid disappearance of lions, which are a rare African subspecies, the Northern lion, Panthera leo leo, and are in immediate danger of extinction in Cameroon and across the rest of their range.

Lions (among other predators) prefer the easy prey that the roaming cattle herds offer, and once this behaviour is learned, the lions often become repeat cattle killers. This has an intolerable economic impact on the herders who choose to poison the cattle carcasses to get rid of the “problem” and simultaneously negatively impact the entire network of carnivores and scavengers (e.g. lion, leopard, hyena, vultures, jackal, serval cat, caracal, civet, mongoose species, etc.). Similar to regular examples reported from Tanzania, Kenya, CAR, etc., we ourselves have apprehended herders with pictures of dead lions on their phones. Cattle herds and lions need to be kept apart, largely by keeping herdsmen and their livestock outside of all protected areas.

During their illegal intrusions, the herdsmen cut down an astronomical number of trees and small shrubs to feed their livestock. Notable are Afzelia africana and Isoberlinia sp., which are the preferred browse for many wild species such as the Kordofan giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis antiquorum), which according to the IUCN, is in critical danger of extinction. Similarly affected is the Lord Derby eland (Taurotragus derbianus gigas), another flagship species, which is also the main animal that attracts tourists, and is thus critical to the chain of income generation that supports the management of and operations in the protected areas, and the fight against conflicts of use & the disappearance of wildlife. Keep in mind that this wildlife constitutes a World Wildlife Heritage, as justified by its many endemic and rare species.

The scale of the migratory herds also results in overgrazing. Overgrazing reduces the diversity of grasses, such that some grass species disappear in favour of non-consumed plants that become invasive due to lack of competition. This phenomenon is well known on domestic cattle farms and in order to prevent permanent loss of diversity is managed for through pasture rotation.

Degradation of the environment and its vegetation as well as the repetitive presence of humans and domestic cattle, cause a reduction of the prime, preferred habitat for respective species, which then become more concentrated as they seek out and use smaller and smaller prime areas. This habitat-reduction and wildlife-concentration process itself results in an increased risk to wildlife populations through the increased risks of spreading diseases (as Nature tries to decrease a species’ population pressure) and by being easier to target by poachers.

Loss of vegetation and transformation of vegetation cover leads to desertification and increased soil erosion by wind and water, which sediments are ultimately deposited in the water courses reducing the depth of water. Siltation and reduced water storage reduces water security, especially during drought years. Reduced water-holding capacity reduces evaporation (which reduces air moisture/rainfall levels) and endless other far-reaching consequences for all the life inhabiting the water and/or terrestrial life dependant ont the presence of water (e.g. riparian vegetation and all the wildlife that drink from rivers and/or live in the riparian vegetation zone), but also for the entire ecological integrity of the area and the entire downstream area. For example, consider the presence of hippos, they are the “lungs” of the river and they play critical ecological roles in the physical and biological functioning of the entire system.

Vegetation and soils is further directly impacted by herders and their livestock who generally use the same trails and corridors when moving through protected areas. This high and unnatural traffic leads to a significant modification of the physical structure of the soils through compaction, but vegetation is also destroyed by trampling.

All told, vegetation, soils, water dynamics, climate, etc. are intrinsically connected. Soil structure and soil health is vital to maintaining the natural vegetation cover and physical soil properties that allow for the complete functioning of many critical processes and ecosystem services. For example, the influx and storage of rainfall, rain runoff and erosion mitigation, organic and mineral nutrient storage, groundwater storage and recharge, healthy macro and micro soil-organism ecosystems (e.g. earthworms, which are a very significant element in the Faro Basin), etc. A further simple example is the penetration of rainwater into the groundwater, a process significantly aided by the presence of earthworms, which if compromised prevents the optimal maintenance of river flows in the dry season and impacts all aquatic life, fish populations, fauna, flora, and humans downstream.

The vast, transient cattle herds also aid directly to global warming through their emissions of methane (CH4), a greenhouse gas, and indirectly through their impacts on vegetation and soil and habitat transformation, compromising the sequestration of soil carbon.

In summary, any process that directly or indirectly affects vegetation and/or soil ultimately has a direct or indirect impact “up” and “down” in the cycle, and which cycle affects itself. Even a limited amount of deforestation and vegetation transformation directly affects every minute aspect of the ecology of its immediate and broader region and should be controlled at all costs.

It is important to note that many herders enter Cameroonian territory illegally, escaping all controls. Directly or indirectly, the herdsmen pose many problems for the internal security of the country and its populations. Herders are also often aggressive towards our anti-poaching units, to the extent that it has lead to murders.

Some herders are involved in smuggling weapons of war, particularly from Nigeria, and fuelling terrorist conflicts on Cameroonian soil. They cross borders along unprotected corridors, particularly inside National Parks, which are mostly devoid of wildlife and poorly monitored.

Herders entering our areas also attract gangs of violent, heavily armed and seasoned bandits who take herders hostage in order to obtain ransoms, without which they proceed to execution.

National security and criminal threats in protected, remote areas make it that much more difficult for economic operators involved in tourism compromising the creation of incomes locally and the inflow of currency at the national level. And if the system ultimately fails, it brings with it the abandonment of presence, and therefore conservation and surveillance activities of the protected areas. Current examples of this are CAR, Burkina Faso, Benin, etc.

While our projects are focussed across Northern Cameroon, our actions will have positive ecological impacts far beyond our borders. Protected area leaseholders in the equatorial forests of Cameroon have already noticed the incursions of M’Bororo herders into the forest zone, the second largest forest massif in Africa after the Democratic Republic of Congo, which ranks fifth in Africa in terms of biological diversity.

These uncontrolled illegal incursions are the direct result of decisions made in Northern Cameroon, and undermine the health of forest species, particularly that of the great apes: the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla gorilla) and chimpanzees (Nigerian-Cameroonian chimpanzee from the north of the Sanaga known as Pan troglodytes ellioti and Central African chimpanzee from the south of the Sanaga known as Pan troglodytes troglodytes).

In addition to all these threats, it is important to remember that this uncontrolled influx of livestock is to the detriment of Cameroonian livestock farmers, since it represents an economic threat to the domestic cattle market.

Illegal Exploitation Of Natural Resources

Poaching is the illegal hunting/harvest of species. ‘Illegal’ is in the context of any of: the species, the sex, the quota, the area, hunting seasons, unlicensed individuals, etc. From a strategic point of view it is necessary to separate the two main types of commercially motivated wildlife poaching. Poaching for the trade of animal products (ivory, skins, bones, teeth, etc.) and poaching for the trade of bush meat.

The poaching of elephants, hippos, crocodiles, lions, and other species cannot be considered territorial. It is opportunistic or premeditated, and occurs randomly throughout the protected areas.

Poaching for the illegal bushmeat trade is generally much more territory related and organised across complicated networks, and it sometimes involves entire illegitimate villages. Moreover, poachers do not select their targets. Females and young are often taken, which is very detrimental to the development of wildlife.

Regardless, it is critical to develop comprehensive field operations built in-line with our general strategies that will combat all forms of wildlife poaching, without distinction or tolerance.

As intimated previously, all wildlife plays a role in the form of ecosystem services; each species is part of a complex chain of processes, and if one of the species in the chain is reduced, the healthy workings of the whole system becomes compromised.

Poachers habitually light bushfires for many reasons: to create new and more accessible pastures for poaching (due to the heat that reactivates plant germination), to flush and move animals out of tall grass to more accessible areas where the wildlife is more vulnerable, and to be able to walk in the bush in greater safety.

These fires directly and indirectly disrupt and complicate the planned conservation-management strategies and operations in our privately protected leases at every level.

Several actors are involved in illegal fishing. Whether they are illegal gold miners who fish for subsistence and the opportunity to prolong their incursions near rivers, or whether they are "simply" illegal subsistence or commercial fishermen, the result is the same.

Small-mesh nets (sometimes mosquito nets that trap the smallest invertebrates) are placed in succession, sometimes the sequence of nets is long enough to cross the entire channel of the river. Nothing gets through. There is no managed or selective harvesting policy and fish are not the only victims. Crocodiles and turtles (both protected) and other reptiles drown in the nets.

The nature of the rivers and the seasons in Northern Cameroon lends itself to styles and scales of illegal fishing that leaves the resource extremely vulnerable to unsustainable fishing. Consider that the reproductive mass of fishes in the protected areas are ‘population reservoirs’ that help maintain the continued existence of the respective species outside of the protected areas, where the lack of any fisheries management has reduced the fish biomass to less than 5% of virgin levels, with resulting negative impacts on the relative ecosystems and losses to the human populations who could benefit from properly protected and managed fisheries.

Uncontrolled and illegal tree felling, for the purpose of making charcoal for cooking or for selling the timber, all depending on the species, causes the same phenomena of desertification, erosion, habitat destruction/transformation, climate changes, etc. as described earlier.

Riverbank collapse, excavation, channel diversion and various other physical processes associated with the mining of alluvial gold and precious stones (often a mineral similar to sapphire), causes rapid erosion and siltation of the rivers and streams, the impacts of which have been mentioned.

Outside of the direct physical impacts resulting from the mining processes there are a whole range of additional serious threats and negative impacts brought about by illegal mining. These include intensive wildlife poaching and illegal fishing, as this allows the miners to travel light and prolong their time near rivers to maximise their yield.

Illegal gold mining is also a soil and water pollution nightmare as miners leave their camps and mining sites littered with used batteries, glass vials, aluminium, non-biodegradable plastics, etc. Some gold miners use motorised pumps resulting in fuel and oil that spills into the soil and water. Dangerous and toxic chemicals are also used in extraction, such as mercury and is extremely poisonous and resilient once it enters the natural environment. All of these impacts have a negative influence on all life, from the source all the way to the ocean

All the forms of poaching and illegal activities and trespassing in protected areas have impacts on the movement of animal species and cause terrible consequences on biodiversity. The simple presence of humans causes wildlife to alter their habits, almost always their own detriment. For example, lions prefer to be near river beds, the same areas frequented by gold miners, but the miners’ presence pushes the lion populations towards other areas where they may be confronted by herders who poison the lions.

Poaching is the illegal hunting/harvest of species. ‘Illegal’ is in the context of any of: the species, the sex, the quota, the area, hunting seasons, unlicensed individuals, etc. From a strategic point of view it is necessary to separate the two main types of commercially motivated wildlife poaching. Poaching for the trade of animal products (ivory, skins, bones, teeth, etc.) and poaching for the trade of bush meat.

The poaching of elephants, hippos, crocodiles, lions, and other species cannot be considered territorial. It is opportunistic or premeditated, and occurs randomly throughout the protected areas.

Poaching for the illegal bushmeat trade is generally much more territory related and organised across complicated networks, and it sometimes involves entire illegitimate villages. Moreover, poachers do not select their targets. Females and young are often taken, which is very detrimental to the development of wildlife.

Regardless, it is critical to develop comprehensive field operations built in-line with our general strategies that will combat all forms of wildlife poaching, without distinction or tolerance.

As intimated previously, all wildlife plays a role in the form of ecosystem services; each species is part of a complex chain of processes, and if one of the species in the chain is reduced, the healthy workings of the whole system becomes compromised.

Poachers habitually light bushfires for many reasons: to create new and more accessible pastures for poaching (due to the heat that reactivates plant germination), to flush and move animals out of tall grass to more accessible areas where the wildlife is more vulnerable, and to be able to walk in the bush in greater safety.

These fires directly and indirectly disrupt and complicate the planned conservation-management strategies and operations in our privately protected leases at every level.

Several actors are involved in illegal fishing. Whether they are illegal gold miners who fish for subsistence and the opportunity to prolong their incursions near rivers, or whether they are “simply” illegal subsistence or commercial fishermen, the result is the same.

Small-mesh nets (sometimes mosquito nets that trap the smallest invertebrates) are placed in succession, sometimes the sequence of nets is long enough to cross the entire channel of the river. Nothing gets through. There is no managed or selective harvesting policy and fish are not the only victims. Crocodiles and turtles (both protected) and other reptiles drown in the nets.

The nature of the rivers and the seasons in Northern Cameroon lends itself to styles and scales of illegal fishing that leaves the resource extremely vulnerable to unsustainable fishing. Consider that the reproductive mass of fishes in the protected areas are ‘population reservoirs’ that help maintain the continued existence of the respective species outside of the protected areas, where the lack of any fisheries management has reduced the fish biomass to less than 5% of virgin levels, with resulting negative impacts on the relative ecosystems and losses to the human populations who could benefit from properly protected and managed fisheries.

Uncontrolled and illegal tree felling, for the purpose of making charcoal for cooking or for selling the timber, all depending on the species, causes the same phenomena of desertification, erosion, habitat destruction/transformation, climate changes, etc. as described earlier.

Riverbank collapse, excavation, channel diversion and various other physical processes associated with the mining of alluvial gold and precious stones (often a mineral similar to sapphire), causes rapid erosion and siltation of the rivers and streams, the impacts of which have been mentioned.

Outside of the direct physical impacts resulting from the mining processes there are a whole range of additional serious threats and negative impacts brought about by illegal mining. These include intensive wildlife poaching and illegal fishing, as this allows the miners to travel light and prolong their time near rivers to maximise their yield.

Illegal gold mining is also a soil and water pollution nightmare as miners leave their camps and mining sites littered with used batteries, glass vials, aluminium, non-biodegradable plastics, etc. Some gold miners use motorised pumps resulting in fuel and oil that spills into the soil and water. Dangerous and toxic chemicals are also used in extraction, such as mercury and is extremely poisonous and resilient once it enters the natural environment. All of these impacts have a negative influence on all life, from the source all the way to the ocean

All the forms of poaching and illegal activities and trespassing in protected areas have impacts on the movement of animal species and cause terrible consequences on biodiversity. The simple presence of humans causes wildlife to alter their habits, almost always their own detriment. For example, lions prefer to be near river beds, the same areas frequented by gold miners, but the miners’ presence pushes the lion populations towards other areas where they may be confronted by herders who poison the lions.

Demographic Pressure & Human Development around Protected Areas

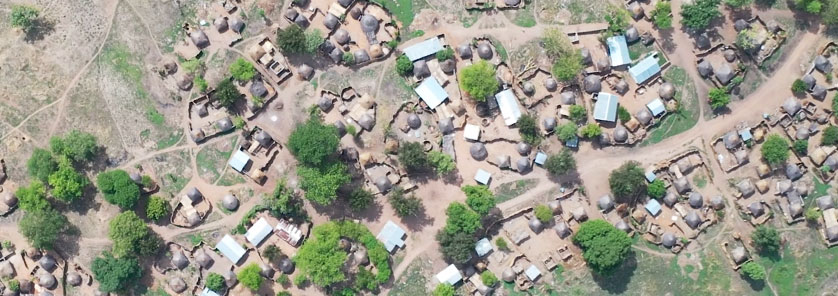

Due to population explosion and a human influx into rural areas surrounding protected areas, existing villages are expanding and new villages are emerging, sometimes illegitimately, and often with the complete complacency of customary authorities.

Village expansion is the primary cause of losses in connectivity between protected areas. Some animal species, such as elephants, often travel more than 25 kilometers per day, and some individual have been recorded travelling nearly 200 kilometres in a day! New villages are appearing in the transhumance corridors that were established as pathways for herders and wildlife between protected areas. In this way animal movements are blocked and elephants no longer travel the same distances. We have observed a sudden withdrawal of elephants from certain protected areas, which leads to imbalances in ecosystem mechanisms. Research from nearly every region of Africa teaches us that the elephants play crucial ecological roles in the balance of savannahs and vegetation dynamics, and confining elephants to smaller areas has many implication.

Geographical isolation is not beneficial to any species as it prevents healthy genetic diversity and favours congenital diseases, from which lions in particular suffer enormously.

As rural human populations increase, so agriculture increases. Some farmers are farming on the "wrong side of the road" and encroaching into protected areas. Others blatantly establish cultivation well within the borders of protected areas. As with many of the elements already discussed, so too does agriculture contribute to desertification, erosion, climate change, etc.

Further threats are brought about through farmers having access to powerful chemical fertilisers and pesticides, often banned substances elsewhere and usually applied in a totally uncontrolled manner, thus polluting and poisoning the soil, plants, and the entire food chain upwards.

Conflicts with wildlife attracted by the cultivation are frequent and result in the execution of the animals involved with impunity.

An additional knock-on effect of agricultural expansion results when village farmers clash with the migrant Fulani herders, pushing the herders to invade protected areas.

Exploding numbers of people typically bring about waste management and pollution issues. Apart from the lack of waste management leading to soil and water pollution, human-animal conflicts and incidences of disease increase as animals are attracted to the waste around villages. Hyenas become particularly problematic, but lions, civets, baboons, monkeys, mongooses, etc. can all bring their own respective sets of risks and problems, the results of which are lose-lose for all parties at best and death at worst.

Domestic dog populations are on the rise in the villages surrounding the protected areas. They typically escape veterinary controls and vaccinations, and are thus prone to contracting and transmitting devastating diseases.

Lion are one of the few felid species susceptible to the terrible distemper, a viral pathogen that is almost always lethal. Distemper is mainly carried by canids (dogs and jackals), but also sometimes by other mammal families such as hyenas. The disease is a paramyxo virus that causes severe neurological, respiratory and gastrointestinal damage, as well as damage to the eyes and skin, particularly under the paw pads, making movement painful for affected individuals, leading to death by starvation. The virus is transmitted through direct contact and ingestion, for example when lions eat weakened or dead dogs. Unlike wild dogs that are already extinct in Cameroon due to distemper, hyenas are less susceptible to contracting the sickness but they are often vectors of the disease through their habit of scavenging at village garbage sites where domestic dogs roam.

Lions are extremely sensitive to the disease and crashes in lions populations have often been reported from elsewhere in Africa, especially when pastoral peoples move into new areas along the borders of protected areas.

For example, in 1991, more than a third of the lion population in Tanzania's Serengeti National Park was ravaged by distemper introduced by the dogs of Maasai pastoralists living on the park's periphery. The contagion spread to other national parks in neighboring countries such as Kenya's Masai Mara National Park, also decimating lion and wild dog populations.

In addition to canine distemper, it is important to emphasise that domestic dogs are also vectors of rabies, which is an always-fatal disease in humans and all other mammals.

Due to population explosion and a human influx into rural areas surrounding protected areas, existing villages are expanding and new villages are emerging, sometimes illegitimately, and often with the complete complacency of customary authorities.

Village expansion is the primary cause of losses in connectivity between protected areas. Some animal species, such as elephants, often travel more than 25 kilometers per day, and some individual have been recorded travelling nearly 200 kilometres in a day! New villages are appearing in the transhumance corridors that were established as pathways for herders and wildlife between protected areas. In this way animal movements are blocked and elephants no longer travel the same distances. We have observed a sudden withdrawal of elephants from certain protected areas, which leads to imbalances in ecosystem mechanisms. Research from nearly every region of Africa teaches us that the elephants play crucial ecological roles in the balance of savannahs and vegetation dynamics, and confining elephants to smaller areas has many implication.

Geographical isolation is not beneficial to any species as it prevents healthy genetic diversity and favours congenital diseases, from which lions in particular suffer enormously.

As rural human populations increase, so agriculture increases. Some farmers are farming on the “wrong side of the road” and encroaching into protected areas. Others blatantly establish cultivation well within the borders of protected areas. As with many of the elements already discussed, so too does agriculture contribute to desertification, erosion, climate change, etc.

Further threats are brought about through farmers having access to powerful chemical fertilisers and pesticides, often banned substances elsewhere and usually applied in a totally uncontrolled manner, thus polluting and poisoning the soil, plants, and the entire food chain upwards.

Conflicts with wildlife attracted by the cultivation are frequent and result in the execution of the animals involved with impunity.

An additional knock-on effect of agricultural expansion results when village farmers clash with the migrant Fulani herders, pushing the herders to invade protected areas.

Exploding numbers of people typically bring about waste management and pollution issues. Apart from the lack of waste management leading to soil and water pollution, human-animal conflicts and incidences of disease increase as animals are attracted to the waste around villages. Hyenas become particularly problematic, but lions, civets, baboons, monkeys, mongooses, etc. can all bring their own respective sets of risks and problems, the results of which are lose-lose for all parties at best and death at worst.

Domestic dog populations are on the rise in the villages surrounding the protected areas. They typically escape veterinary controls and vaccinations, and are thus prone to contracting and transmitting devastating diseases.

Lion are one of the few felid species susceptible to the terrible distemper, a viral pathogen that is almost always lethal. Distemper is mainly carried by canids (dogs and jackals), but also sometimes by other mammal families such as hyenas. The disease is a paramyxo virus that causes severe neurological, respiratory and gastrointestinal damage, as well as damage to the eyes and skin, particularly under the paw pads, making movement painful for affected individuals, leading to death by starvation. The virus is transmitted through direct contact and ingestion, for example when lions eat weakened or dead dogs. Unlike wild dogs that are already extinct in Cameroon due to distemper, hyenas are less susceptible to contracting the sickness but they are often vectors of the disease through their habit of scavenging at village garbage sites where domestic dogs roam.

Lions are extremely sensitive to the disease and crashes in lions populations have often been reported from elsewhere in Africa, especially when pastoral peoples move into new areas along the borders of protected areas.

For example, in 1991, more than a third of the lion population in Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park was ravaged by distemper introduced by the dogs of Maasai pastoralists living on the park’s periphery. The contagion spread to other national parks in neighboring countries such as Kenya’s Masai Mara National Park, also decimating lion and wild dog populations.

In addition to canine distemper, it is important to emphasise that domestic dogs are also vectors of rabies, which is an always-fatal disease in humans and all other mammals.